Northern Epirus

- Note: For the autonomous state formed in the region at 1914, see: Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus.

|

The region of Epirus, stretching across Greece and Albania.

|

Northern Epirus (Greek: Βόρειος Ήπειρος, Vorios Ipiros, Albanian: Epiri i Veriut) is a term used to refer to those parts of the historical region of Epirus, in the western Balkans, that are part of the modern Albania. The term is used mostly by Greeks and is associated with the existence of a substantial ethnic Greek population in the region. It also has connotations with political claims on the territory on the grounds that it was held by Greece and was sporadically a Greek autonomous state during parts of the 20th century. The term is typically rejected by most Albanians for its irredentist associations. However, in 1987, Greece and Albania ended their state of war and Greece officially rejected any territorial claims against Albania.[2]

Geography

The term Epirus is used both in the Albanian and Greek language, but in Albanian refers only to the historical and not modern region.

Geographically, the region has varied in its depiction from time to time. In antiquity the northern borders of Epirus (and of the ancient Greek world) were located in the Gulf of Oricum[3][4]. According to the 20th century definition, Northern Epirus stretches from the Llogara (Acroceraunian) mountains north of Himara southward to the Greek border, and from the Ionian coast to Lake Prespa. The Northern Epirote homeland in South Albania is characterized by steep limestone ridges that parallel the coast, with high valleys that raise to the Pindus mountains inland[5]. The main rivers of the area are: Vjosë (Greek: Αώος, Aoos) his tributary Drino (Greek: Δρίνος, Drinos) and northeast Osum (Greek: Άψος Apsos) and Devoll (Greek: Εορδαϊκός Eordaikos). Some of the cities and towns of the region are: Himarë, Sarandë, Delvinë, Gjirokastër, Tepelenë, Përmet, Leskovik, Ersekë, Korçë, Bilisht and the once prosperous town of Moscopole.

For Albania, this region is part of several folkloric regions, like Laberia and Southwest Albania.

History

Mythological foundations and ancient settlements

.jpg)

Many of the region’s settlements are related with the Trojan Epic cycle. Elpenor from Ithaca, in charge of Locrians and Abantes from Evia, founded the cities of Orikum and Thronium on the bay of Vlorë. Amantia in the mainland was founded by Avantes from Thronium. Neoptolemos of the Aekid dynasty, in charge of Myrmidones, founded a settlement which in classical antiquity would become known as Bylliace (near Apollonia). Aeneas and Helenus founded Vouthroton (modern Butrint). Moreover, a son of Helenus, named Chaon became the ancestral leader of the Epirot tribe of the Chaonians.[3]

Other ancient settlements in the area were Onchemos (modern Sarande) , Phoenice, Antigoneia (near modern Gjirokastër), Antipatrea (modern Berat), Amantia, Nikea, Pelion (in Dessaretis), Kemara (modern Himarë). On the other hand, Greek colonists (mostly Corinthians and Eleans) founded a number of coastal cities: Avlon (modern-day Vlorë), Apollonia, and Epidamnus.

Ancient period

The earliest recorded inhabitants of the region (c. 7th century BC) were the Chaonians, one of the main Greek tribes of ancient Epirus, and the region was known as Chaonia. Apart from the Chaonians, which were the most significant Epirotic tribe in the area, other Epirotic tribes in northern Epirus were the Antinanes, Parauaei, Prasaivoi and northernmost tribe the Dexari (or Desarrerai). During the 7th century B.C. Chaonian rule was dominant over the region and their power stretched from the Ionian coast to the region of Korçë in the east. Tumulus II in Kuc i Zi near modern Korçë is to date to that age (ca. 650 B.C.) and it is claimed that it belonged to Chaonian nobles.[3]

In 330 BC, the Epirotic tribes were united under a single kingdom under the Aeacid ruler Alcetas II (of the Molosians Epirotes), and in 232 B.C. the Epirotes established the 'Epirotic League' (Greek: Κοινό Ηπειρωτών), with Phoenice as one of its centres. As a united state Epirus was a significant power of the Greek world until the Roman conquest in 167 BC.[6]

Roman and Byzantine period

Christianity first spread in Northern Epirus during the 1st century AD, but prevailed during the 4th century. Notable Epirote martyrs were Eleftherios of Avlon, and Isavros. The presence of the local bishops in the Ecumenical Synods (already from 381 A.D.) proves that the new religion was well organized and already widely spread inside the Greek world of the Roman and post-Roman period.[7]

While Epirus vetus corresponded to the Ancient Greek region Epirus Nova corresponded[8] to a part of Illyria that was now was partly Hellenic[9] and partly Hellenized[9].This Greek[10] area was the line of division[10] between the provinces of Illyricum and Macedonia and its borders was the Drin River in modern north Albania.

When the Roman Empiresplit into East and West, Northern Epirus became part of the East Roman (Byzantine) Empire; the region witnessed the invasions of several nations: Visigoths, Avars, Slavs, Normans, Serbs, Albanian clans and various Italian city-states and dynasties (14th century). However the region’s culture remained closely tied to the centers of the Greek world, and retained its Greek character through the medieval period.

In 1204, the region was part of the Despotate of Epirus, a successor state of the Byzantine Empire. Despot Michael I found there strong Greek support in order to facilitate his claims for the Empire’s revival. In 1281, a strong Sicilian force that planned to conquer Constantinople was repelled in Berat after a series of combined operations by local Epirotes and Byzantine troops. In 1345, the region was invaded by the Serbs of Stefan Dušan. However, the Serbian rulers retained much of the Byzantine tradition and used Byzantine titles to secure the loyalty of the local population. At the same time Venetians controlled various ports of strategic importance, like Vouthroton, but the Ottoman presence became more and more intense and finally in the middle of the 15th century the entire area came under Turkish rule.

Ottoman period

.jpg)

After the Ottoman annexation local authorities were, exclusively Muslim, whether Albanian or Turkish. However, there were specific parts of Northern Epirus that enjoyed local autonomy (Himarë, Drouvian, Moscopole). In spite of the Ottoman dominance, Christianity prevailed in many areas and became an important reason for preserving the Greek language, which was also the language of trade.[11]

Inhabitants of the region participated in the Greek enlightenment. One of the leading figures of that period, the Orthodox missionary Cosmas of Aetolia, traveled and preached over the country. It is believed that he founded more than 200 Greek schools until his execution by Turkish authorities near Berat.[12] In addition, the first printing press in the Balkans, after that of Constantinople, was founded in Moscopole (nicknamed ‘New Athens’) by a local Greek[13]. From the mid-18th century trade was thriving and a great number of educational facilities and institutions were founded throughout the rural regions and the major urban centers as benefactions by several Epirot entrepreneurs[14].

During this period a number of uprisings against the Ottoman empire periodically broke up. In the Orlov Revolt (1770) several units of Riziotes, Chormovites and Himariotes supported the armed operation. Northern Epirus took also part in the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830): many locals revolted, organized armed groups and joined the revolution.[15] The most distinguished personalities were the engineer Konstantinos Lagoumitzis[16] from Hormovo and Michail Spyromilios from Himarë. The latter was one of the most active generals of the revolutionaries and participated in several major armed conflicts, such as the Third Siege of Messolonghi, where Lagoumitzis was the defenders' chief engineer. M. Spyromilios also became a prominent political figure after the creation of the modern Greek state and discreetly supported the revolt of his compatriots in Ottoman-occupied Epirus in 1854, during the Crimean War[17]. Another uprising in 1878, in Saranda-Delvina region, with the revolutionaties demanding union with Greece, was suppressed by the Ottoman forces, while in 1881, the Treaty of Berlin awarded Greece parts of southern Epirus.

Balkan Wars (1912-1913)

With the outbreak of the First Balkan War (1912–1913) and the Ottoman defeat, the Greek army entered the region. The outcome of the following Peace Treaties of London[18] and of Bucharest[19], signed at the end of the Second Balkan War, was unpopular among both Greeks and Albanians, as settlements of the two people existed on both sides of the border: Northern Epirus, already under the control of the Greek army, was awarded to the newly found Albanian State, while the southern part was ceded to Greece.

Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus (1914)

In accord with the claims of the Greek population, the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus, centered in Gjirokastër, was declared in March 1914 by the pro-Greek party, which was in power in southern Albania at that time[20]. Georgios Christakis-Zografos, a distinguished Epirot politician from Lunxhëri, took the initiative and became the head of the Republic. In May, autonomy was confirmed with the Protocol of Corfu, signed by Albanian and Epirot representatives and approved by the Great Powers. The signing of the Protocol ensured that the region would have its own administration, recognized the rights of the local Greeks and provided self government under nominal Albanian sovereignty[20].

However, the agreement was never implemented, because when World War I broke out in July, Albania collapsed. Although short-lived,[20][21] the state of North Epirus left behind a substantial historical record.

World War I and following peace treaties (1914-1921)

Under an October 1914 agreement among the Allies, Greek forces re-entered Northern Epirus and Italians seized the Vlore region[20]. During the war the French Army occupied the area around Korçë in 1916, and established the Republic of Koritsa. The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 awarded the area to Greece after World War I, however, political developments such as the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-22 and, crucially, Italian, Austrian and German lobbying in favor of Albania resulted in the area being ceded to Albania in 1921.

Interwar period (1921-1939) - Zog's regime

The Albanian Government, with the country's entrance to the League of Nations (October 1921), made the commitment to respect the social, educational, religious rights of every minority.[22] However, only a limited area (in the Districts of Gjirokastër, Sarandë and four villages in Himarë region consisting of 15,000 inhabitants[2]) was recognized as a Greek minority zone. The following years, measures were taken to suppress[23] the minority's education. The Albanian state viewed Greek education as a potential thread to its territorial integrity[2]. Greek schools were either closed or forcibly converted to Albanian schools and teachers were expelled from the country. The 360 schools of the pre-World War I period were reduced dramatically in the following years and education in Greek was finally eliminated altogether in 1935:[24][25]

1926: 78, 1927: 68, 1928: 66, 1929: 60, 1930: 63, 1931: 64, 1932: 43, 1933: 10, 1934: 0

With the intervention of the League of Nations in 1935, a limited number of schools, and only of those inside the minority's recognize zone, reopened.

During that period the Albanian state led to efforts to establish an independent orthodox church (contrary to the Protocol of Corfu), thereby reducing the influence of Greek language in the country's south. According to a 1923 law, priests who were not Albanian speakers, as well as not of Albanian origin, were excluded from this new autocephalous church[2].

World War II (1939-1945)

In 1939, Albania became an Italian protectorate and was used to facilitate military operations against Greece the following year. The Italian attack, launched at October 28, 1940 was quickly repelled by the Greek forces. The Greek army, although facing a numerically and technologically superior army, counterattacked and in the next month managed to enter Northern Epirus. So, in Northern Epirus thus became the site of the first clear setback for the Axis powers. However, after a six months period of Greek administration the Nazi German invasion of Greece followed (April 1941) and Greece capitulated.

Following Greece's surrender, Northern Epirus again became part of the Italian-occupied Albanian protectorate. Many Northern Epirotes formed resistance groups and organizations in the struggle against the occupation forces. At 1942 the Northern Epirote Liberation Organization (EAOVI, also called MAVI) was formed.[26] Some others joined the left-wing Albanian National Liberation Army, in which they formed a separate battalion (named Thanasis Zikos).[27]

During October 1943-April 1944, the Albanian collaborationist organization Balli Kombëtar with support of Nazi German officers mounted a major offensive in Northern Epirus and fierce fighting occurred between the EAOVI and them. The results were devastating. During this period over 200 Greek populated towns and villages were burned or destroyed, 2,000 Northern Epirotes were killed, 5,000 imprisoned and 2,000 taken hostages to concentration camps. Moreover, 15,000 homes, schools and churches were destroyed. Thirty thousand people had to find refuge in Greece during and after that period, leaving their homeland[28][29]. When the war ended, a United States Senate resolution demanded the cession of the region to the Greek state, but according to the following post war international peace treaties it remained part of the Albanian state.[30]

Cold War period (1945-1991) - Hoxha's regime

General violations of human and minority rights

After World War II, Albania was governed by a Communist regime led by Enver Hoxha, which suppressed the minority (as the rest of the population) and took measures to disperse it or at least keep it loyal to Albania,[31] such as: pupils were taught only Albanian history and culture at primary level, the minority zone was reduced from 103 to 99 villages (excluding Himarë), many Greeks were forcibly removed from the minority zones to other parts of the country losing their fundamental minority rights (as a product of communist population policy, an important and constant element of which was to pre-empt ethnic sources of political dissent), Greek place-names were changed and Greeks were pressed enormously to change their names into Albanian ones,[32] while use of the Greek language, prohibited everywhere outside the minority zones, was prohibited for many official purposes within them as well.[11][33][34]

On the other hand Enver Hodxa favored few specific members of the minority offering them prominent positions within the country's system, as part of his 'tokenism' policy. However, when the Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev asked about giving more rights, even autonomy, to the minority the answer was negative[27].

Censorship

Strict censorship was introduced in Socialist Albania as early as 1944,[35] while the press remained under tight dictatorial control right up until the end of the Eastern Bloc (1991).[36] In 1945, Laiko Vima, a propaganda organ of the Party of Labour of Albania, was the only printed media that was allowed to be puplished in Greek and was accessible only to Gjirokastër District.[37]

Stalinist Albania, had become increasingly paranoid and isolated after de-Stalinization and the death of Mao Tse Tung (1976),[38] restricted visitors to 6,000 per year, and segregated those few that traveled to Albania.[39]

Resettlements

Although the Greek minority acquired some limited rights, during that period a number of Muslim Cham Albanians, that were expelled from Greece after World War II, were given new homes in the area, diluting the local Greek element[40]. Moreover, at this period a number of new settlements, consisting of Muslim settlers, were created as a buffer zone between the recognized 'minority zone' and regions of unclear ethnic consciousness[24].

Isolation and labour camps

The country was virtually isolated and common penalties for attempts to escape the country, for ethnic Greeks, were executions of the offenders and exile for their families, usually in mining camps in central and northern Albania[41]. The regime maintained twenty-nine prisons and labour camps throughout Albania, that were filled with more than 30,000 'enemies of the state' year after year. It was unofficially reported that a large percentage of the imprisoned were ethnic Greeks [42].

Prohibition of religion

The state attempted to suppress any religious practice (both public and private), adherence to which was considered "anti-modern" and dangerous to the unity of the Albanian state. The process started in 1949[24], with the confiscation and nationalization of Church property and intensified in 1967 when the authorities conducted a violent campaign to extinguish[43] religious life in Albania, claiming that it had divided the Albanian nation and kept it mired in backwardness. Student agitators combed the countryside, forcing Albanians and minorities, including the Greek one to quit practicing their faith. All churches, mosques, monasteries and other religious institutions were closed or converted into warehouses, gymnasiums, and workshops. Clergy were imprisoned, owning an icon became an offense that could be prosecuted under Albanian law. The campaign culminated in an announcement that Albania had become the world's first atheistic state, a feat touted as one of Enver Hoxha's greatest achievements.[44] In this respect, the campaign against religions hit ethnic Greeks disproportionately, since affiliation to the Eastern Orthodox rite has traditionally been a strong component of Greek identity.[45]

- See also: Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania, Religion in communist Albania

Post-communist period (1991-present)

With the fall of communism (1991), Orthodox churches were reopened and religious practices were permitted after 35 years of strict prohibition. Moreover, Greek-language education was initially expanded. However, in November 1993, when Greek-Albanian tensions escalated, seven schools were forcibly closed by the Albanian police.[46] A purge of ethnic Greeks in the professions in Albania continued in 1994, with particular emphasis in law and the military.[47] Although relations between Albania and Greece have greatly improved in recent years, the Greek minority in Albania continues to suffer discrimination[27][48] as the Albanian government continues to restrict[34] the teaching of the Greek language. Tensions continue on specific occasions, as during the local government elections in Himara in 2000, where a number of incidents of hostility towards the Greek minority took place, as well as with the defacing of signposts written in Greek in the country's south by Albanian nationalist elements.[49]

Demographics

In Albania, Greeks are considered a "national minority". There are no reliable[34] statistics on the size of any ethnic minorities in Albania, as the Albanian government does not include them on the census. The Albanian government is not going to conduct an official census on ethnicity. Some commentators allege that this is out of fear that a considerable part of the population will register themselves as Greek.[50]

According to data presented to the 1919 Paris Conference, by the Greek side, the Greek minority numbered 120,000,[51] and the last census to include data on ethnic minorities conducted in 1989 under the communist regime cites only 58,785 Greeks although the total population of Albania had tripled in the meantime.[51] However, the area studied was confined to the southern border, and this estimate is considered to be low. Under this definition, minority status was limited to those who lived in 99 villages in the southern border areas, thereby excluding important concentrations of Greek settlement and making the minority seem smaller than it is.[34] Sources from the Greek minority have claimed that there are up to 500,000 Greeks in Albania, or 12% of the total population at the time (from the "Epirot lobby" of Greeks with family roots in Albania).[52]

In a 1995 ethnological study, the number of ethnic Greeks in the Northern Epirus alone, are estimated at 40,000, while in the rest of the country there are further 20,000 Greeks[11]. The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization estimates the Greek minority at approximately 70,000 people.[53] Other independent sources estimate that the number of Greeks in Northern Epirus is 117,000 (about 3.5% of the total population),[54] a figure close to the estimate provided by The World Factbook (2006) (about 3%). But this number was 8% by the same agency a year before.[55][56] The total population of Northern Epirus is estimated to be around 577,000 (2002), with main ethnic groups being Albanians, Greeks and Vlachs [57].

Impact on Albanian-Greek relations

Tensions between Greece and Albania over the treatment of the Greek population persisted well after the end of the World War II, the formal state of war between the two countries being lifted only as late as 1987. Relations reached a low point after the fall of Albania's Communist régime in 1991. In 1993, Albania deported the Greek Orthodox Archimandrite of Gjirokastër for what is described as seditious behaviour. The crisis in relations was exacerbated in late August 1994, when an Albanian court sentenced five members (a sixth member was added later) of the ethnic Greek organization Omonoia to prison terms of 6–8 years on charges of treason, because they demanded that Northern Epirus be granted to Greece, and for illegal carrying of arms.[58] Greece responded by freezing all EU aid to Albania, sealing its border with Albania, and between August-November 1994, expelling over 115,000 illegal Albanian immigrants, a figure quoted in the US Department of State Human Rights Report and given to the American authorities by their Greek counterpart.[59] In December 1994, however, Greece began to permit limited EU aid to Albania, while Albania released two of the Omonoia defendants and reduced the sentences of the remaining four.

Today, relations have significantly improved; Greece and Albania signed a Friendship, Cooperation, Good Neighbourliness and Security Agreement on March 21, 1996. Additionally, Greece is Albania's main foreign investor, having invested more than 400 million dollars in Albania, Albania's second largest trading partner, with Greek products accounting for some 21% of Albanian imports, and 12% of Albanian exports coming to Greece, and Albania's fourth largest donor country, having provided aid amounting to 73.8 million euros.[60]

The Northern Epirote issue at present

Education shall be free. In the schools of the Orthodox communities the instruction shall be in Greek. In the three elementary classes Albanian will be taught concurrently with Greek. Nevertheless, religious education shall be exclusively in Greek.

Liberty of language:The permission to use both Albanian and Greek shall be assured, before all authorities, including the Courts, as well as the elective councils.

These provisions will not only be applied in that part of the province of Corytza now occupied militaritly by Albania, but also in the other southern regions.[61]

While violent incidents have declined in recent years, the ethnic Greek minority has pursued grievances with the government regarding electoral zones, Greek-language education, property rights. On the other hand minority representatives complain of the government's unwillingness to recognize the possible existence of ethnic Greek towns outside communist-era 'minority zones'; to utilize Greek on official documents and on public signs in ethnic Greek areas; to ascertain the size of the ethnic Greek population; and to include more ethnic Greeks in public administration.[62] There have been many minor incidents between the Greek population and Albanian authorities over issues such as the alleged involvement of the Greek government in local politics, the raising of the Greek flag on Albanian territory, and the language taught in state schools of the region; however, these issues have, for the most part, been non-violent.

'Minority zone'

The Albanian Government continues to use the term "minority zones", in violation to human rights issues, to describe the southern districts consisting of 99 towns and villages, which they have recognized majorities of ethnic Greeks. In fact it continues to contend that all those belonging to national minorities are recognised as such, irrespective of the geographical areas in which they live. However, the situation is somewhat different in practice. This results in a situation in which the protection of national minorities is subject to overly rigid geographical restrictions restricting access to minority rights outside these zones. One of the major fields that it has a practical application is that of education.[64][65]

Minority's representation on local and state politics

The minority's sociopolitical organization from promotion of Greek human rights, Omonoia, founded in January 1991, took an active role on minority issues. Omonoia was banned in the parliamentary elections of March 1991, because it violated the Albanian law which forbade 'formation of parties on a religious, ethnic and regional basis'. This situation resulted in a number of strong protests not only from the Greek side, but also from international organizations. Finally, on behalf of Omonoia, the Unity for Human Rights Party contested at the following elections, a party which represents that Greek minority in the Albanian parliament[66].

Politicians from the Greek minority have also become MPs for other parties, as Spiro Ksera, Viktor Gumi and Kosta Barka for DPA; and Anastas Angjeli, Stefan Cipa, Vasilika Hysi-Barka, Vangjel Tavo and Luiza Papathanasi-Xhuvani for SPA.

In more recent years, tensions have surrounded the participation of candidates of the Unity for Human Rights Party in Albanian elections. In 2000, the Albanian municipal elections were criticised by international human rights groups for "serious irregularities" reported to have been directed against ethnic Greek candidates and parties.[67] The most recent municipal elections held in February 2007 saw the participation of a number of ethnic Greek candidates, with Vasilis Bolanos being re-elected mayor of the southern town of Himarë despite the governing and opposition Albanian parties fielding a combined candidate against him. Greek observers have expressed concern at the "non-conformity of procedure" in the conduct of the elections.[68]

In 2004, there were five ethnic Greek members in the Albanian Parliament, and two ministers in the Albanian cabinet.[69]

Land distribution and property in post-communist Albania

The return to Albania of ethnic Greeks that were expelled during the past regime seemed possible after 1991. However, the return of their confiscated properties is even now impossible, due to Albanian's inability to compensate the present owners. Moreover, the full return of the Orthodox Church property also seems impossible for the same reasons[46].

Education

Greek education in the region was thriving during the late Ottoman period (18th-19th centuries). When the First World War broke out in 1914, 360 Greek language schools were functioning in Northern Epirus (as well as in Elbasan, Berat, Tirana) with 23,000 students.[70] During the following decades the majority of Greek schools were closed and Greek education was prohibited in most districts. In the post-communist period (after 1991), the reopening of schools was one of the major objectives of the minority. In April 2005 a bilingual Greek-Albanian school in Korca,[71] and after many years of efforts, a private Greek school was opened in the Himara municipality in spring of 2006.[72]

Official positions

Albania

In Albanian bibliography it is widely claimed that the Greek minority as it currently exists was the result of population movements under the Ottoman empire, and the great majority of the Greeks arrived in modern Albania as indentured labourers in the time of the Ottoman beys denying any link with local ancient Greek presence[73].

In 1994 the Albanian authorities admitted for the first time that Greek minority members exist not only in the designated 'minority zones' but all over Albania[74].

Greece

In 1991, the Greek Prime Minister Konstantinos Mitsotakis specified that the issue, according the Greek minority in Albania, focuses on 6 major topics that the post-communist Albanian government should deal with[46]:

- The return of the confiscated property of the Orthodox Church and the freedom of religious practice.

- Functioning of Greek language schools (both public and private) in all the areas that Greek populations are concentrated.

- The Greek minority should be allowed to found cultural, religious, educational and social organizations.

- Illegal dismissals of members of the Greek minority from the country’s public sector should be stopped and same rights for admission should be granted (on every level) for every citizen.

- The Greek families that left Albania during the communist regime (1945–1991), should be encouraged to return to Albania and acquire their lost properties.

- The Albanian government should take the initiative to conduct a census on ethnological basis and give its citizens the right to choose without limitations their ethnicity.

Incidents

In April 1994, Albania announced that unknown individuals attacked a military camp near the Greek-Albanian border (Peshkëpi incident), with two soldiers killed. Responsibility for the attack was taken by MAVI (Northern Epirus Liberation Front), which officially ceased to exist since the end of World War II. This incident triggered a serious crisis between Albanian-Greek relations[74].

Gallery

Konstantinos Zappas |

Evangelos Zappas |

Georgios Christakis-Zografos |

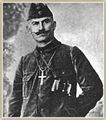

Spyromilios |

Spyros Spyromilios |

Pyrros Dimas |

Sotiris Ninis |

1-drachma value of the infantryman issue of March 1914 |

Flag stamp, 5 lepta of 1914 |

Occupation overprint on 3-lepta stamp of Greece of 1916 |

See also

- Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus

- Protocol of Corfu

- Albanisation

- Chameria

- Epirus (region)

- Northern Epirotes

- Postage stamps and postal history of Epirus

- List of Greek countries and regions

References

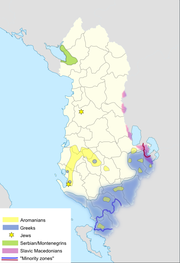

- ↑ Following G. Soteriadis: “An Ethnological Map Illustrating Hellenism In The Balkan Peninsula And Asia Minor” London: Edward Stanford, 1918. Image:Hellenism in the Near East 1918.jpg

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Roudometof, Robertson 2001: 223

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3: part 3, 2000

- ↑ Smith, William (2006). A New Classical Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography, Mythology and Geography. Whitefish, MT, USA: Kessinger Publishing, LLC. pp. 423.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the stateless nations: ethnic and national groups around the world. James Minahan. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002. ISBN 0313323844

- ↑ P. R. Franke, "Pyrrhus", in The Cambridge Ancient History VII Part 2: The Rise of Rome to 220 BC: 469, ed. Frank William Walbank. Cambridge University Press, 1984. ISBN 0521234468.

- ↑ Bowden 2003

- ↑ Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians, 1992,ISBN-0631198075,Page 210

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 American journal of philology, Τόμοι 98-99,by JSTOR (Organization), Project Muse,1977,page 263, the partly Hellenic and partly Hellenized Epirus Nova

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Migrations and invasions in Greece and adjacent areas by Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond,1976,ISBN-0815550472,page 54,The line of division between Illyricum and the Greek area Epirus nova

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Winnifrith 2002

- ↑ Stavro Skendi. The Albanian National Awakening, 1878-1912. Princeton University Press, 1967.

- ↑ Greek, Roman and Byzantine studies. Duke University. 1981

- ↑ Katherine Elizabeth Fleming. The Muslim Bonaparte: diplomacy and orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 9780691001944

- ↑ Pappas, Nicholas Charles (1991). Greeks in Russian military service in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Nicholas Charles Pappas. pp. 318, 324. ISBN 0521234476. http://books.google.com/?id=eAW5AAAAIAAJ&cd=1&dq=.

- ↑ Surrealism in Greece: An Anthology. Nikos Stabakis. University of Texas Press, 2008. ISBN 0292718004

- ↑ The military in Greek politics: from independence to democracy. Thanos Veremēs. Black Rose Books, 1998 ISBN 1551641054

- ↑ Clogg 2002: 79. "In February 1913, Greek troops captured Ioannina, the capital of Epirus. The Turks recognised the gains of the Balkan allies by the Treaty of London of May 1913."

- ↑ Clogg 2002: 81. "The Second Balkan War was of short duration and the Bulgarians were soon forced to the negotiating table. By the Treaty of Bucharest (August 1913) Bulgaria was obliged to accept a highly unfavorable territorial settlement, although she did retain an Aegean outlet at Dedeagatch (now Alexandroupolis in Greece). Greece's sovereignty over Crete was now recognized but her ambition to annex Northern Epirus, with its substantial Greek population, was thwarted by the incorporation of the region into an independent Albania."

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Stickney 1926

- ↑ Petiffer 2001: "In May 1914, the Great Powers signed the Protocol of Corfu, which recognized the area as Greek, after which it was occupied by the Greek army from October 1914 until October 1915."

- ↑ Griffith W. Albania and the Sino-Soviet Rift. Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1963: 40, 95.

- ↑ Petiffer 2001: "Under King Zog, the Greek villages suffered considerable repression, including the forcible closure of Greek-language schools in 1933-1934 and the ordering of Greek Orthodox monasteries to accept mentally sick individuals as inmates."

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 King, Mai, Schwandner-Sievers 2005: 173-194

- ↑ George H. Chase. Greece of Tomorrow, ISBN 1406707589: 41.

- ↑ Pyrrhus J. Ruches. Albania's Captives. Argonaut, 1965 (University of California).

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Miranda Vickers & James Petiffer 1997

- ↑ Albania in the Twentieth Century, A History: Volume II: Albania in Occupation and War, 1939-45. Owen Pearson. I.B.Tauris, 2006. ISBN 1845111044.

- ↑ Pyrrhus J. Ruches. 1965: 172 "The entire carnage , arson and imprisonment suffered by the hands of Balli Kombetar...schools burned".

- ↑ Milica Zarkovic Bookman (1997). The demographic struggle for power: the political economy of demographic engineering in the modern world. Routledge. p. 245. ISBN 9780714647326. http://books.google.com/?id=q_Mv2IcQ0pQC&dq=.

- ↑ Clogg 2002: 203 "Like all Albanians, the members of the Greek minority had suffered severe repression during the communist era and cross-border family visits had been out of the question. Although basic linguistic, educational and cultural rights were conceded there had been attempts to disperse the minority pressure had been applied on its members to adopt authentically "Illyrian" names."

- ↑ Clogg 2002

- ↑ Petiffer 2001: "...under communism, pupils were taught only Albanian history and culture, even in Greek-language classes at the primary level."

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Petiffer 2001: "...the area studied was confined to the southern border fringes, and there is good reason to believe that this estimate was very low"."Under this definition, minority status was limited to those who lived in 99 villages in the southern border areas, thereby excluding important concentrations of Greek settlement in Vlorë (perhaps 8000 people in 1994) and in adjoining areas along the coast, ancestral Greek towns such as Himara, and ethnic Greeks living elsewhere throughout the country. Mixed villages outside this designated zone, even those with a clear majority of ethnic Greeks, were not considered minority areas and therefore were denied any Greek-language cultural or educational provisions. In addition, many Greeks were forcibly removed from the minority zones to other parts of the country as a product of communist population policy, an important and constant element of which was to pre-empt ethnic sources of political dissent. Greek place-names were changed to Albanian names, while use of the Greek language, prohibited everywhere outside the minority zones, was prohibited for many official purposes within them as well."

- ↑ Frucht, Richard C. (2003). Encyclopedia of Eastern Europe: From the Congress of Vienna to the Fall of Communism. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 148. ISBN 0203801091

- ↑ Frucht, Richard C. (2003). Encyclopedia of Eastern Europe: From the Congress of Vienna to the Fall of Communism. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 640. ISBN 0203801091

- ↑ Valeria Heuberger, Arnold Suppan, Elisabeth Vyslonzil (1996) (in German). Brennpunkt Osteuropa: Minderheiten im Kreuzfeuer des Nationalismus. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. p. 71. ISBN 9783486561821. http://books.google.com/?id=edAu3dxEwwgC.

- ↑ Olsen, Neil (2000). Albania. Oxfam. p. 19. ISBN 0855984325

- ↑ Turnock, David (1997). The East European economy in context: communism and transition. Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 0415086264

- ↑ David Shankland. Archaeology, anthropology, and heritage in the Balkans and Anatolia Isis Press, 2004. ISBN 9789754282801, p. 198.

- ↑ Miranda Vickers & James Petiffer 1997: 190

- ↑ Working Paper. Albanian Series. Gender Ethnicity and Landed Property in Albania. Sussana Lastaria-Cornhiel, Rachel Wheeler. September 1998. Land Tenure Center. University of Wisconsin. "Hoxha's regime maintained an extensive gulag...40 percent.

- ↑ Petiffer 2001: "...onset in 1967 of the campaign by Albania’s communist party, the Albanian Party of Labour (PLA), to eradicate organised religion, a prime target of which was the Orthodox Church. Many churches were damaged or destroyed during this period, and many Greek-language books were banned because of their religious themes or orientation. Yet, as with other communist states, particularly in the Balkans, where measures putatively geared towards the consolidation of political control intersected with the pursuit of national integration, it is often impossible to distinguish sharply between ideological and ethno-cultural bases of repression. This is all the more true in the case of Albania’s anti-religion campaign because it was merely one element in the broader "Ideological and Cultural Revolution" begun by Hoxha in 1966 but whose main features he outlined at the PLA’s Fourth Congress in 1961.

- ↑ Miranda Vickers & James Petiffer 1997: "...with the demolition and the subsequent demolition of many churches, burning of religious books… general human rights violations. Christians could not mention Orthodoxy even in their own homes, visit their parents’ graves, light memorial candles or make the sign of the Cross."

- ↑ Minority Rights Group International, World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Albania : Greeks, 2008. Online. UNHCR Refworld

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Valeria Heuberger, Arnold Suppan, Elisabeth Vyslonzil (1996) (in German). Brennpunkt Osteuropa: Minderheiten im Kreuzfeuer des Nationalismus. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. p. 74. ISBN 9783486561821. http://books.google.com/?id=edAu3dxEwwgC&vq=nordepirus

- ↑ Miranda Vickers & James Petiffer 1997: 198

- ↑ Petiffer 2001: "In 1991, Greek shops were attacked in the coastal town of Saranda, home to a large minority population, and inter-ethnic relations throughout Albania worsened".

- ↑ World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous People: Albanian overview: Greeks.

- ↑ Migration and Ethnicity in Albania: Synergies and Interdependencies. Kosta Barjaba. Watson Institute for International Studies. Nonetheless, it appears that the Albanian government is not going to conduct an official census, which would clarify the numbers. The Albanian government fears that if a census were adopted, a considerable part of the population would be registered as Greek.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "Bilateral relations between Greece and Albania". http://www.mfa.gr/www.mfa.gr/en-US/Policy/Geographic+Regions/South-Eastern+Europe/Balkans/Bilateral+Relations/Albania/. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- ↑ "Country Studies US: Greeks and Other Minorities". http://countrystudies.us/albania/49.htm. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- ↑ "UNPO". http://www.unpo.org/member_profile.php?id=23. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- ↑ Jelokova Z., Mincheva L., Fox J., Fekrat B. (2002). "Minorities at Risk (MAR) Project : Ethnic-Greeks in Albania". Center for International Development and Conflict Management, MAR Project, University of Maryland, College Park. http://www.cidcm.umd.edu/inscr/mar/data/albgrks.htm. Retrieved July 26, 2006.

- ↑ CIA World Factbook (2006). "Albania". https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/al.html. Retrieved July 26, 2006.

- ↑ The CIA World Factbook (1993) provided a figure of 8% for the Greek minority in Albania.

- ↑ James Minahan, Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nation, 2002, pg. 547. Greenwood Press [1]

- ↑ Clogg 2002: 214. "This war of words culminated in the arrest by the Albanian authorities in May of six members of the Onomoia, the main Greek minority organization in Albania. At their subsequent trial, five of the six received prison sentences of between six and eight years for treasonable advocacy of the secession of "Northern Epirus" to Greece and the illegal possession of weapons.

- ↑ Greek Helsinki Monitor: Greeks of Albania and Albanians in Greece, September 1994.

- ↑ Greek Ministry for Foreign Affairs: Bilateral relations between Greece and Albania.

- ↑ Ruches, Pyrros (1965). Albania's Captives. Chicago, USA: Argonaut. pp. 92–93

- ↑ Minority Rights Group International, World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Albania: Greeks, 2008. UNHCR Refworld

- ↑ Second Report Submitted By Albania Pursuant to Article 25, Paragraph 1, of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

- ↑ Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities: Second Opinion on Albania 29 May 2008. Council of Europe: Secretariat of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

- ↑ Albanian Human Rights Pracitces, 1993. Author: U.S. Department of State. January 31, 1994.

- ↑ Petiffer 2001: "Following strong protests by the Conference on Security... this decision was revered.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch Report on Albania

- ↑ Erlis Selimaj (2007-02-19). "Albanians go to the polls for local vote". Southeast European Times. http://setimes.com/cocoon/setimes/xhtml/en_GB/features/setimes/features/2007/02/19/feature-02. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ↑ Albania: Profile of Asylum claims and country conditions. United States Department of State. March 2004, p. 6.

- ↑ Nußberger Angelika, Wolfgang Stoppel (2001) (in German). Minderheitenschutz im östlichen Europa (Albanien). Universität Köln. pp. 75. http://www.uni-koeln.de/jur-fak/ostrecht/minderheitenschutz/Vortraege/Albanien/Albanien_Stoppel.pdf

- ↑ "Albanische Hefte. Parlamentswahlen 2005 in Albanien" (in German). Deutsch-Albanischen Freundschaftsgesellschaft e.V.. 2005. pp. 32. http://www.albanien-dafg.de/downloads/AH-3-2005.pdf.

- ↑ Gregorič 2008: 68

- ↑ Petiffer 2001: 4-5

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 King, Mai, Schwandner-Sievers 2005: 73

Bibliography

History

- Iorwerth E. S. Edwards, John Boardman, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond (2000). The Cambridge Ancient History - The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries B.C. Part 3: Volume 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521234476. http://books.google.com/?id=0qAoqP4g1fEC.

- Bowden, William (2003). Epirus Vetus: The Archaeology of a Late Antique Province. Duckworth. ISBN 9780715631164. http://books.google.com/?id=ElFoAAAAMAAJ&dq=.

- Stickney, Edith Pierpont (1926). Southern Albania or Northern Epirus in European International Affairs, 1912–1923. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804761710. http://books.google.com/?id=n4ymAAAAIAAJ.

- Ruches, Pyrrhus J. (1965). Albania's captives. Chicago: Argonaut. http://books.google.com/?id=01eQAAAAIAAJ&q=.

- Clogg, Richard (2002). Concise History of Greece (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80872-3. http://books.google.com/?id=H5pyUIY4THYC.

- Victor Roudometof, Roland Robertson (2001). Nationalism, globalization, and orthodoxy: the social origins of ethnic conflict in the Balkans. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313319495. http://books.google.com/?id=I9p_m7oXQ00C&dq=.

- Winnifrith, Tom (2002). Badlands-borderlands: a history of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0715632019. http://books.google.com/?id=dkRoAAAAMAAJ.

Current topics

- Miranda Vickers, James Pettifer (1997). Albania: from anarchy to a Balkan identity. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 0715632019. http://books.google.com/?id=9IbgsDdeVxsC.

- Sussana Lastaria-Cornhiel, Rachel Wheeler (1998). "Working Paper. Albanian Series. Gender Ethnicity and Landed Property in Albania". Land Tenure Center. University of Wisconsin. http://minds.wisconsin.edu/bitstream/handle/1793/21961/48_wp18.pdf?sequence=1.

- Petiffer, James (2001). "The Greek Minority in Albania - In the Aftermath of Communism". Surrey, UK: Conflict Studies Research Centre. http://kms1.isn.ethz.ch/serviceengine/Files/ISN/38652/ipublicationdocument_singledocument/5494CBC6-4F56-4EFD-B6DB-7FB1EC46CC11/en/2001_Jul_2.pdf.

- Russell King, Nicola Mai, Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers (Ed.) (2005). The New Albanian Migration. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 9781903900789. http://books.google.com/?id=05Mw4-b9oN0C.

- Gregorič, Nataša (2008). "Contested Spaces and Negotiated Identities in Dhermi/Drimades of Himare/Himara area, Southern Albania". University of Nova Gorica. http://www.p-ng.si/~vanesa/doktorati/interkulturni/3GregoricBon.pdf.

Further reading

- Fred, Abrahams (1996). Human rights in post-communist Albania. Human Rights Watch/Helsinki. ISBN 9781564321602. http://books.google.com/?id=MkmGHvI-RyUC.

- Triadafilopoulos, Triadafilos (November 2000). "Power politics and nationalist discourse in the struggle for 'Northern Epirus': 1919-1921". Journal of Southern Europe and the Balkans 2 (2): 149–162. doi:10.1080/713683343.

- Minahan, James (2002). Encyclopedia of the stateless nations: ethnic and national groups around the world. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 218. ISBN 0313323844. http://books.google.com/?id=K94wQ9MF2JsC.

External links

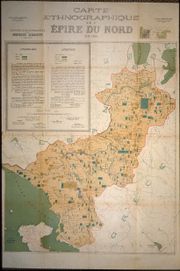

- Ethnographic map of Albania and neighbors, showing concentration of Greeks in Northern Epirus

- UNPO profile of the Greek minority in Albania

- Albania: the Greek minority by Human Rights Watch

- Assessment for Greeks in Albania by the Minorities at Risk (MAR) Project

- Greeks of Albania and Albanians in Greece by the Greek Helsinki Monitor

- Southern Albania, Northern Epirus: Survey of a Disputed Ethnological Boundary by Tom J. Winnifrith

- Research Foundation on Northern Epirus (I.B.E.)

- Northern Epirus: Hellenism Through Time

- Northern Epirot Youth

- Northern Epirus News Agency

- The Government of Epirus in Exile

- Unofficial Flag

|

||||||||||||||||||||